Sentencing Bias in the U.S. | Why Justice Isn’t Blind

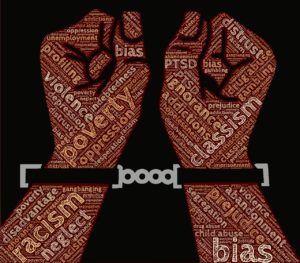

President Obama, in a speech at Howard University in 2016, provided some thoughtful insight on the existence of implicit bias in our criminal justice system, stating, “And we knew . . . that even the good cops with the best of intentions – including, by the way, African-American police officers – might have unconscious biases, as we all do.” Justice Anthony Kennedy recently opined in a Court opinion that “Bias is easy to attribute to others and difficult to discern in oneself.” But what about sentencing bias? Bias, implicit and explicit, is something that has been, and continues to be, a major challenge to our criminal justice system. Justice should be blind, and we should strive for those words etched on the front of the U.S. Supreme Court – “Equal Justice Under Law.” Yet, time and again our criminal justice seems to fall far short of the mark.

One in every 10 black men in his 30s is incarcerated on any given day. More than 60% of people in prison in the U.S. are people of color. Hispanic men are close to two times more likely than white men to be incarcerated. These statistics seem to suggest that sentencing bias against minorities still plays a big role in sentencing decisions today.

The Color of Justice – a Recent Report Revealing Continuing Bias in Sentencing

The Sentencing Project, a national non-profit organization focused on U.S. criminal justice issues, recently put out a report on sentencing bias in state courts, titled “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons.” Focused on state criminal sentencing, this report reinforces what we generally believe about our current criminal justice system: it is not entirely blind, but rather disfavors people of color.

what we generally believe about our current criminal justice system: it is not entirely blind, but rather disfavors people of color.

America remains the world leader in incarcerating its own citizens. More than 1.3 million people are held in state prisons around the country. Just like the first step to solving a problem is acknowledging there is a problem to begin with, meaningful reform to our criminal justice system will not occur without acknowledging the disparities of prison inmates based on race and ethnicity. Sentencing bias is a problem.

The “Color of Justice” report focuses on state prisoners because the majority of prisoners are sentenced at the state level rather than the federal level. Some of the key findings of the report are as follows.

- African-Americans are incarcerated at a rate 5.1 times the rate of whites. In five states – Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin – the disparity is greater than 10 to 1.

- The prison population in twelve states in the U.S. is over 50% African-American. In fact, Maryland tops the nation with a prison population that is 72% African-American.

- In eleven states, 1 in 20 African-American males is in prison.

- States vary widely with regard to racial disparity in prison. For example, the African-American/white ratio is 12.2 to 1 in New Jersey, but only 2.4 to 1 in Hawaii.

- Latinos are imprisoned at a rate 1.4 times the rate of whites. The Hispanic/white ratio is particularly high in Massachusetts, 4.3 to 1; and Connecticut, 3.9 to 1.

What Are Some of the Drivers of Sentencing Bias?

The data clearly shows that there is a pervading racial disparity in the prison populations throughout the United States. Even though the public, and some policymakers, understand the problems with mass incarceration, the disparities and sentencing bias persist.

Three explanations for the disparity seem to frequently emerge from studies done by criminologists on the subject:

- Policies and practices that drive disparity. One example, taken from the federal sentencing world, is the substantially higher criminal sentences for crack cocaine compared to powder cocaine. Because the majority of crack cocaine users are African-American, despite the fact that whites and African-Americans use cocaine at roughly the same rate, the harsher crack cocaine sentences go predominantly to African-Americans.

- Implicit bias and stereotypes in decision-making. Recent studies show that judges, both federal and state, have equal or greater implicit racial biases than members of the general public. In addition, research on pre-sentence reports demonstrates that people of color are frequently given harsher sanctions because they are viewed as being a greater risk to public safety. The harsher sentences for people of color has a snowball effect because the general public, seeing a higher rate of minorities in prison, perceives people of color as a higher risk, thereby perpetuating the problem.

- Structural disadvantages for communities of color. Disparities in prison are partially because of the greater relative poverty, employment, housing, and family differences in some communities of color. Approximately 62% of African-Americans reside in highly segregated, inner-city neighborhoods, which experience a high degree of violent crime. By contrast, a majority of whites live in so-called “highly advantaged” neighborhoods, which has a lower rate of violent crime. In sum, many people of color begin life on an uneven playing field, and those inequalities carry forward to choices on whether to commit crime.

These persistent societal issues are not easy to overcome. There are some suggestions on how to begin reform. Pulling back on the harshness of drug offenses, ending mandatory minimum laws, scaling back excessively long prison sentences when possible, and giving bias training to law enforcement decision makers, are good places to start.

In the meantime, those who are currently incarcerated need quality representation to take advantage of whatever laws or release programs are currently available. Consider retaining an experienced sentencing advocate like Brandon Sample, Esq. Brandon Sample can aggressively advocate for you. Call 802-444-HELP today for a free consultation, or submit an online request for a free consultation.

Additional Resources

Recommended for you

Amendment 782 Motion Reconsideration

Reinaldo Rivera moved for 18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(2) relief based on Amendment 782 to the Guidelines, commonly known as “drugs minus 2.” The district court granted the motion and reduced his sentence to 420 months from LIFE. But in doing so, the district court believed Rivera’s mandatory minimum was 30 years for his CCE conviction.…

Drug Treatment And Vocational Training Improper Sentencing Considerations

Christopher Thornton moved for a downward variance at sentencing arguing, among other things, that “in-prison treatment during the proposed thirty-eight months would help mitigate any potential risk he posed to the community.” The district court denied the motion, but in doing so said that Thornton had “mental-health issues, and he needs drug treatment” and that…